27 May 1224: Cathal Crovderg [‘Redhand’] O'Conor, king of Connacht, son of Turlough and brother of Rory O'Conor (the last Ard Rí or 'High King' of Ireland), died at the age of 72. He was the last of the great Irish Kings. His death opened the way for the Norman takeover of Connacht.

King Cathal had to play what might be described in today's terms as a masterly game of 'Realpolitic' in his time as King. He was faced with a range of enemies both internal and external who wished to bring him down. Depending on circumstances he was prepared to 'switch sides' and play one off against another. He built alliances with Thomand (north Munster), with Tir Owen and Fermanah in the North and sometimes with the Anglo-Norman invaders. But he was not averse to throwing himself at the mercy of the Justicar in Dublin when he was forced to flee his own kingdom.

From his base west of the river Shannon he was forced to deal with the Norman invaders. He was a competent leader despite problems, avoiding major conflicts and winning battles. Ua Conchobair attempted to make the best of the new situation with Ireland divided between Norman and Gaelic rulers.

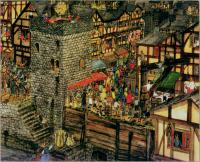

He succeeded as head of the O'Conors on the death of his brother Rory in 1198. But by the time Cathal became king the power and influence of his family was much reduced. Now they ruled just in Connacht and that with difficulty. The early part of his reign was passed in contests with the Anglo-Normans and with his nephew Cathal Carrach, who at one time succeeded in expelling him from his territories. In 1201, however, Cathal Crovderg, with the assistance of the Anglo Norman De Burghs, defeated and slew his nephew in battle near Boyle. On King John's arrival in Ireland in 1210, he paid him homage, and by the surrender of a portion of his territories, secured to himself a tolerably peaceful old age. He died in the abbey of Knockmoy (having assumed the habit of a Grey Friar) in 1224. The principal abode of the heads of the O'Connor family at this period was at Rathcroghan [above], near Tulsk, in the County of Roscommon.

He founded Ballintubber Abbey in 1215, and was succeeded by his son, Aedh mac Cathal Crobdearg Ua Conchobair. His wife, Mor Ní Briain, was a daughter of King Domnall Mór Ua Briain of Thomond, died in 1218.

By the end of his Life he had come to accept the primacy of the King of England as also 'Lord of Ireland' as a political necessity and only wished to have his son recognised by King Henry III of England as his successor.

He wrote to King Henry in 1224 shortly before his death:

'To his dear Lord Henry,by the grace of God King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, Count of Anjou, from his faithful King of Connacht, greeting, and bond of sincere affection with faithful obedience.'

'We feel sure that you have heard, through the trusty men and counsellors of your father and your own, how that we did not fail to give faithful and devoted service to the Lord John, your father of happy memory ; and since his death, as your trusty servants stationed in Ireland know and have learned, we are not failing to give devoted obedience to you, nor do we wish ever as long as we live to fail you. Wherefore, although we possess a charter for the land of Connacht from the Lord your father given to ourselves and our heirs, and by name to Od [Aedh] our son and heir...'

LETTER FROM CATHAL "CROVDEARG" O'CONOR, KING OF CONNACHT, TO HENRY III, circa 1224

Taken from A History of Ireland by Eleanor Hull

His eulogy in the Annals of Connacht relates the attributes that a true King was expected to portray to his People:

'A great affliction befell the country then, the loss of Cathal Crobderg son of Toirrdelbach O Conchobair, king of Connacht;

the king most feared and dreaded on every hand in Ireland;

the king who carried out most plunderings and burnings against Galls and Gaels who opposed him;

the king who was the fiercest and harshest towards his enemies that ever lived;

the king who most blinded, killed and mutilated rebellious and disaffected subjects;

the king who best established peace and tranquility of all the kings of Ireland;

the king who built most monasteries and houses for religious communities;

the king who most comforted clerks and poor men with food and fire on the floor of his own habitation;

the king whom of all the kings in Ireland God made most perfect in every good quality;

the king on whom God most bestowed fruit and increase and crops;

the king who was most chaste of all the kings of Ireland;

the king who kept himself to one consort and practised continence before God from her death till his own;

the king whose wealth was partaken by laymen and clerics, infirm men, women and helpless folk, as had been prophesied in the writings and the visions of saints and righteous men of old;

the king who suffered most mischances in his reign, but God raised him up from each in turn;

the king who with manly valour and by the strength of his hand preserved his kingship and rule.

And it is in the time of this king that tithes were first levied for God in Ireland. This righteous and upright king, this prudent, pious, just champion, died in the robe of a Grey Monk, after a victory over the world and the devil, in the monastery of Knockmoy, which with the land belonging to it he had himself offered to God and the monks, on the twenty-seventh day of May as regards the solar month and on a Monday as regards the week-day, and was nobly and honourably buried, having been for six and thirty years sole monarch of the province of Connacht.

So says Donnchad Baccach O Maelchonaire in his poem on the Succession of the Kings:

‘The reign of Red-hand was a pleasant reign, after the fall of Cathal Carrach; he ruled for sixteen and twenty prosperous calm years.’

And he was in the seventy-second year of his age, as the poet Nede O Maelchonaire says: ‘Three years and a half-year, I say, was the life of Red-hand in Cruachu till the time that his father died in wide-stretching Ireland.’

He was born at Port Locha Mesca and fostered by Tadc O Con Chennainn in Ui Diarmata, and it was sixty-eight years from the death of Toirrdelbach to the death of Cathal Crobderg, as the chronicle shows.'

The Annals of Connacht

.jpg/390px-EI-AOE_V803_Viscount_Aer_Lingus_LPL_16MAR66_(5641658470).jpg)