3 & 4 (N.S.) January 1602 - 23-24 December 1601 [O.S]: The Battle of Kinsale/Cath Chionn tSáile was fought on this day.

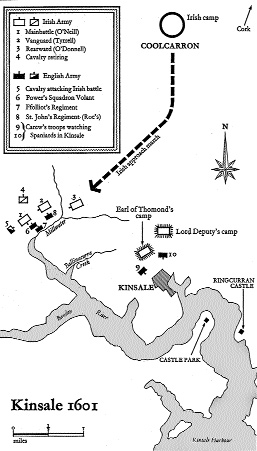

Probably the most decisive battle in Irish History took place on this day. The forces of the Irish under the Earl of Tyrone, Aodh (Hugh) O’Neill, and his ally Aodh ‘Red Hugh’ O’Donnell attacked the English lines surrounding the besieged town of Kinsale and were defeated. Inside was the Spanish garrison under Don John Aquila. The siege had begun two months before when the Spanish had landed at this small fishing port on Ireland’s south east coast. They had been sent by King Philip II of Spain to aid the Catholic Irish in their revolt against the Protestant Queen Elizabeth of England.

News quickly spread throughout the Country of their landing and both the Irish and the English made haste their forces to march south and meet Aquila either as friends or enemies. The English were under the command of Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy. Mountjoy in Dublin was nearer to Kinsale than the northern leaders in Ulster and consequently got his forces to Kinsale first. He quickly laid siege to Kinsale. However he was not strong enough to risk taking it by storm. With the place blocked by land and by sea he intended to starve the garrison out and hope that the Irish would not be able to envelop him from the outside as well. In the event the Irish came south in sufficient numbers to make it very difficult to re-supply his forces. Both side’s forces suffered from want and lack of shelter but Mountjoy’s men felt it more and thousands of the besiegers of Kinsale died from cold and disease.

The Irish on the outside were not equipped to be so far from their base of operations in Ulster and could not remain indefinitely on the outside unless they had hope of Victory. Eventually they agreed with the Spanish commander to launch an assault if they could be guaranteed that a sally would be made by Aquila’s men to support them. But getting the timing right was crucial and with the English between them it was fright with difficulty.

There was some dispute amongst the Irish as to the best course of action to follow, with O’Donnell for making a determined attack while O’Neill counselled caution. In all probability the decisions of the Irish leaders to attack when they did was taken in light of their dwindling supplies and the desperation of their men to march North to their homes (where English pressure and intrigue was intense). It was a calculated gamble to meet the English in the open as their men were used to a different kind of warfare, one of the woods, the bogs and the rough terrain where English cannon and cavalry were of limited use.The northern leaders chose to bring their forces up to the English lines under cover of night but such a night march is never an easy venture and in the dark columns became disorientated.

They spent much time in the early hours in dispute and contention, which arose between them. The two noble hosts and armies marched at last side by side and shoulder to shoulder together, until they happened to lose their way and go astray, so that their guides and pathfinders could not hit upon the right road, though the winter night was very long and though the camp which they were to attack was very near them, it was not until the time of sunrise on the next day, so that the sun was shining brightly on the face of the solid earth when O’Neills forces found their own flank at the lord Deputy’s camp, and they retired a short distance while their ranks and order would be reformed, for they had left the first order in which they had been drawn up through the straying and the darkness of the night….

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh Ui Domhnaill (The Life of Red Hugh O’Donnell) - Lughaidh O Cleirigh

Formed up in crude and unwieldy copies of the Spanish ‘Tercios’ [blocks of fighting men] it would appear the Irish could not manoeuvre in front of Mountjoy’s fixed positions in a manner that could hope to inflict upon the enemy any significant casualties. In the event Mountjoy was on the ball and took the initiative, using his cannon and cavalry to good effect and scattering the Irish columns and riding down the survivors with his Horse.

They were not long considering them till they fired a thick shower of round balls [to welcome the Irish] from clean, beautiful big guns, with well oiled mechanisms and from finely ridged, costly muskets, and from sharp-aiming, quick firing matchlocks, and they threw upon them every other kind of shot and missile besides. Then burst out over the walls against them nimble troops, hard to resist, of active steady cavalry, who up to that were longing for the order to test the seed of their high galloping horses on the plain. They allowed their foot to follow after for they were certain that the hail of spherical bullets and the force attack of the troops would make destructive gaps in front of them among their enemies. Both armies were mingled together, maiming and wounding each other so that many were slain on both sides.

But in the end O’Neill’s forces were defeated, an unusual thing with them, and they fled swiftly away from the place, and they way the hurry urged them was to pour in on top of O’Donnell’s forces who happened to be east of them and had not yet come to the field of battle. When the routed army of O’Neill, and the troops of the Lord Deputy’s army following them, and swiftly smiting their rear, broke into the midst of O’Donnell’s people, wavering and unsteadiness seized on the soldiers, fright and terror on their horses and though it was their desire and their duty to remain on the field of battle, they could not.

O Cleirigh

Inside Kinsale nothing stirred and De Aquila claimed he was not aware what the Irish planned to do that day. He soon after surrendered and was allowed to depart for Spain with his men. The morale of the Irish in revolt never recovered after this huge setback and the forced departure of the expeditionary force sent by the King of Spain to help them. O’Donnell almost immediately took ship for Spain to organise another expedition but was poisoned there by English agents. O’Neill returned North and fought on until 1603 when he surrendered to Mountjoy. Remarkably he got his personal Estates back and with a fair degree of local control again in his hands.

But his days were numbered as English Law was gradually extended into Ulster and his authority continually undermined. Fearing imprisonment and execution on trumped up accusations he fled to the Continent in 1607 in the famous ‘Flight of the Earls’. He ended his days in Rome as a charge on the Spanish Monarchy but under the immediate protection of the Pope. He died and was buried there in 1616 - still plotting to regain his lost lands.