Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Tuesday, 29 November 2022

29 November 1641: Battle of Julianstown/ Cath Baile Iúiliáin in County Meath was fought on this day. Julianstown is situated on the River Nanny, which flows into the sea at Laytown about 3 km away. It was along this way that a relief force from Dublin was dispatched by the Lords Justice Borlase and Parsons to help relieve the town of Drogheda, which was in danger of encirclement by the Irish insurgents of Sir Phelim O’Neill.

He directed a force led by Colonel Rory O'More / Ruairí Óg Ó Mórdha to prevent this column from ever reaching Drogheda and O’More kept close to the main road north from Dublin to enable him to strike at a moment of his own choosing. The Irish troops actually engaged though were under the tactical command of one Colonel Plunkett on the day apparently. As luck would have it the weather this day was cold and foggy and the English, even though warned beforehand by Viscount Gormanstown that they were in immediate danger, stumbled into what was in effect an ambush. The Irish waited until the moment was ripe and then they uttered a great shout of their war cries and rushed out of the mists to fall upon the hapless enemy cutting them to pieces. Some 600 of the enemy were left dead on the road and surrounding fields while the few survivors fled back in the direction they came.

...the rebels forces who now furiously approached with a great shout and a lieutenant giving out the unhappy word of counter march all the men possessed as it were of a panic fear began somewhat confusedly to march back; but they were so much amazed with a second shout given by the rebels, who, seeing them in disorder followed close on, as not withstanding that they had gotten into a ground of great advantage, they could not be persuaded to stand a charge, but betook themselves to their heels, and so the rebels fell sharply on, as their manner is, upon the execution.

Bellings in Gilbert’s Irish Confederation

Prisoners were taken but according to Temple the attackers ‘spared very few or none that fell into their hands, but such as were Irish whose lives they preserved’

Sir John Temple The Irish Rebellion (London, 1646)

The commander of the Royalist force was Sir Patrick Wemyss, Scottish born but his mother was related to the Earls of Desmond. He was Captain-Lieutenant in the Army of King Charles I and was a close associate of the Earl of Ormond. He has left us the only known eye witness account of the battle. He wrote to Ormond on the following day:

I will now tell you of our misfortune. We lodged last night at Balrederie (Balrothery,), as my officers could not make the men march to Drogheda. We were informed that the enemy were upon us, but they did not fall on us. Next day on the march, we sent out scouts and saw a few rebels, but after crossing the Julanstowne bridge, I saw them advancing towards us in as good order as ever I saw any men. I viewed them all, and to my conjecture they were not less than 3,000 men....

I drew up the troops on their front, and told the captains that we were engaged in honour to charge them, and that I would charge them first with those horse I had. They promised faithfully to second me. But when I made the trumpet sound, the rebels advanced towards us in five great bodies of foot; the horse, being on both wings, a little advance before the foot; but just as I was going to charge, the troop cried unto me and told me the foot had left their officers, thrown down their arms, and took themselves to running. It was useless to fight, so I withdrew as best I could and escaped with a loyal remnant to Drogheda.

Two of my troop whose horses went lame were left behind. I hear however that they are safe, except for their clothes, which were taken from them, not by the rebels, but by natives as they passed through the village. All our arms and ammunition are in the rebel's hands. We can get no food here for man or horse.

Calendar of State Papers Ireland 1641

The defeat of the troops sent from Dublin was a powerful factor in influencing the Catholic Old English of Meath to throw in their lot with their fellow co-religionists to halt any further encroachments upon their Civil and Religious Liberties by the English Protestants. This was a real catalyst in the history of Ireland as it was the first time that the people descended from the English colonisers of the 12/13th centuries had come together in a common cause with the native Gaelic Irish to defy the Crown.

Monday, 28 November 2022

Sunday, 27 November 2022

27 November 789 AD: Feast day of Saint Vergilius (Fergal) the Irish missionary and astronomer died at Salzburg, Austria on this day. He was said to have been a descendant of Niall of the Nine Hostages. His original Christian name was Fergal. In the "Annals of the Four Masters" and the "Annals of Ulster" he is mentioned as Abbot of Aghaboe, in County Laois.

He left Ireland, intending to visit the Holy land, but he made it no further than Paris where Pepin, then mayor of the Palace under Childeric III, received him with great favour. After spending two years at Cressy, near Compiegne, he went to Bavaria, at the invitation of Duke Otilo, and within a year or two was made Abbot of St. Peter's at Salzburg. Out of humility, he "concealed his orders", and had a bishop named Dobdagrecus, a fellow countryman, appointed to perform his episcopal functions for him.

It was while Abbot of St. Peter's that he came into collision with St. Boniface. A priest having, through ignorance, conferred the Sacrament of Baptism using, in place of the correct formula, the words Baptizo te in nomine patria et filia et spiritu sancta. Vergilius held that the sacrament had been validly conferred. Boniface complained to Pope Zachary. The latter, however, decided in favour of Vergilius.

Later on, St. Boniface accused Vergilius of teaching a doctrine in regard to the rotundity of the earth, which was: "Contrary to the Scriptures". Pope Zachary's decision in this case was that "if it be proved that he held the said doctrine, a council be held, and Vergilius expelled from the Church and deprived of his priestly dignity"

'Unfortunately we no longer possess the treatise in which Vergilius expounded his doctrine. Two things, however, are certain: first, that there was involved the problem of original sin and the universality of redemption; secondly, that Vergilius succeeded in freeing himself from the charge of teaching a doctrine contrary to Scripture. It is likely that Boniface misunderstood him, taking it for granted, perhaps, that if there are antipodes*, the "other race of men" are not descendants of Adam and were not redeemed by Christ. Vergilius, no doubt, had little difficulty in showing that his doctrine did not involve consequences of that kind.'

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15353d.htm

After the martyrdom of St. Boniface, Vergilius was made Bishop of Salzburg (766 or 767) and laboured successfully for the up building of his diocese as well as for the spread of the Faith in neighbouring heathen countries, especially in Carinthia.. In 1233 he was canonized by Gregory IX. His doctrine that the Earth is a sphere was derived from the teaching of ancient geographers, and his belief in the existence of the antipodes was probably influenced by the accounts, which the ancient Irish voyagers gave of their journeys.

* The antipodes of any place on the Earth is the point on the Earth's surface which is diametrically opposite to it. Two points that are antipodal to each other are connected by a straight line running through the centre of the Earth

Saturday, 26 November 2022

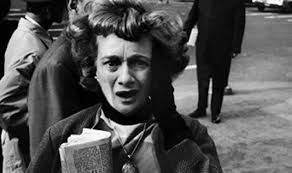

26 November 1972: Dramatic and bloody events occurred in the City of Dublin on this day: A Bombing was carried out on a crowded City Centre cinema. There was also the arrest and imprisonment for contempt of Court of one Kevin O’Kelly, a well known RTE journalist, plus an unsuccessful attempt by the IRA to rescue one of their top men, Seán Mac Stiofáin [above], from the Mater Hospital in the north inner City.

At 1.25 a.m. a bomb exploded in a laneway connecting Burgh Quay to Leinster Market. It was placed beside the rear exit door of the Film Centre cinema, O’Connell Bridge House. A late film was in progress: there were 3 staff and approximately 156 patrons in the cinema at the time of the explosion. No one was killed in the blast, but some 40 people were taken to hospital for treatment, some very badly injured. It is believed that agent provocateurs sent over from Britain were responsible for this attack.

The events leading to O’Kelly and Mac Stiofáin’s arrests had begun on Sunday 19 November when RTE Radio broadcast a report based on an interview by Kevin O'Kelly with the IRA Chief of Staff, Seán Mac Stiofáin. The leading Republican figure had been apprehended soon afterwards and brought before the Courts. O'Kelly was found guilty of contempt of Court when, during the conduct of the trial of Mac Stiofáin, he refused to identify the defendant as the subject of that interview.

The IRA Leader had embarked upon a Hunger Strike soon after he was arrested. He was convicted of being ‘a member of an unlawful organisation’ and as his condition was deteriorating he was sent to the Mater Hospital where he was to be placed under observation. That Sunday afternoon a crowd of about 7,000 people had gathered outside the GPO and marched to the hospital to demand his release. Later that night a rescue party of eight IRA men, two disguised as Priests and the others as Hospital Doctors tried to free Mac Stiofáin but were themselves captured. Two of the men had guns, and shots were exchanged with Special Branch detectives, resulting in minor injuries to a detective, two civilians and one of the raiders.

The Prisoner was then transferred by helicopter to the Curragh General Military Hospital to serve the rest of his six month sentence - while his erstwhile rescuers were each sent down for seven years for their audacity when they in turn faced the Courts.

Friday, 25 November 2022

Thursday, 24 November 2022

24 November 1865: The dramatic rescue of James Stephens of the IRB from the Richmond Prison [above], Dublin on this day. The Fenian Leader was rescued from Richmond Prison in Dublin after only a few weeks captivity. He had been held only a few weeks when his escape was organised from without and within the prison itself. Inside the Richmond were John J. Breslin who was a hospital warder and a Daniel Byrne, an ordinary warder. The two men were sworn members of the I.R.B. and willing to help.

On the outside the acting leader of the Organisation was Colonel Thomas Kelly and he helped put together a support team from within the Fenians to ensure that once on the outside Stephens remained free. At great risk Breslin managed to take wax impressions of the two keys he needed, one for Stephens cell, which was held in the Governors office and another for one of the outer doors. On the night of the actual rescue everything went according to plan. Only one other prisoner (a common criminal) was incarcerated on the same wing as Stephens and he wisely kept his mouth shut.

Once outside Stephens was ushered away to a safe house in the Summerhill area of the City where he remained for a number of months. The British put a price of £1,000 on his head but even this amount did not yield any informer willing to betray him. He eventually he made his way to Paris where he lived for many years and after a brief stay in Switzerland he returned home in 1891 and was left undisturbed by the Castle. He died in 1901.

It is curious to note that his escape from incarceration was an event that many Irish People at the time erroneously believed to have been acquiesced in by the British Government of the day. It was certainly an easy triumph for Irish Republicans that hugely embarrassed the occupying power. The locale of Richmond Prison later became Wellington Barracks and after Independence was known as Griffith Barracks. Today the site is occupied by Griffith College on the South Circular Rd, Dublin.

Wednesday, 23 November 2022

23 November 1867: Execution of the Manchester Martyrs William Philip Allen, Michael Larkin and Michael O’Brien. They were publicly hanged for their alleged role in the rescue of Fenian prisoners in which a Constable Brett was fatally wounded. Although neither Larkin, Allen and O’Brien had fired the fatal shot nor had they had any intention to kill anybody, they were hanged as accessories to the death of the policeman.

The martyrs were hanged in front of the New Bailey prison in Salford, Manchester. Part of the wall was removed so that the public could witness the event. The morning of their execution was a cold and foggy one. Large crowds, marshalled by police and troops had assembled to witness the spectacle. Shortly after 8 O’Clock the men were led out and hanged, the bodies dropping out of sight into the pit below and out of sight of the onlookers.

They were buried in quicklime in Strangeways Prison. Today they rest in a mass grave in Blackley Cemetery, Plot number C.2711. Manchester. Their noble stand in the dock and on the gallows inspired T. D. Sullivan to pen the famous ballad ‘God save Ireland’.

When the news of their execution reached Ireland, solemn funeral processions were held, and three coffinless hearses proceeded to Glasnevin Cemetery, followed by 60,000 mourners. Allen was a native of Tipperary, O'Brien came from Ballymacoda, Co. Cork, and Larkin from Lusmagh, Co Offaly.

It was widely felt amongst the Irish both at home and abroad that these men were wrongly hanged as it was not their intention to kill and nor had they. The brave and courageous stand they took in the Dock and upon the Gallows inspired Irish People around the World and helped to restore morale in the wake of the abortive Rising of 1867.

Ironically the first prisoner to utter these immortal words was one Edward O'Meagher Condon a veteran of the US Civil War & who had his death sentence commuted to Life Imprisonment. Prior to his sentencing, Condon addressed the Court in a famous speech in which he said 'You will soon send us before God, and I am perfectly prepared to go, I have nothing to regret, or to retract, or take back. I shall only say -GOD SAVE IRELAND!

Another man Thomas Maguire was released from captivity as the case against him was so poor even the English Media felt he should be set free!

Numerous monuments were erected to the Martyrs in the wake of their deaths across Ireland incl. a symbolic grave to these brave men in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.

The famous song, which their sacrifice gave birth to, opens with the lines:

High upon the gallows tree, swung the noble-hearted three,

By the vengeful tyrant, stricken in their bloom.

But they met him face to face with the courage of their race,

And they went with souls undaunted to their doom.

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

22 November 1963: President John Fitzgerald Kennedy was killed by an assassin's bullets as his motorcade wound through Dallas, Texas on this day. Kennedy was the youngest man elected President and he was the youngest to die. He was hardly past his first thousand days in office. His great grandparents hailed from Co Wexford and had fled Ireland in the 1840s to Boston, Massachusetts.

His Inaugural Address offered the memorable injunction: "Ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country."

His untimely and brutal death triggered a wave of shock and grief throughout Ireland that very night as word rapidly spread across the airwaves and by word of mouth that the President had succumbed to his wounds. He had visited this Country only a few months previously and had been met with a huge and ecstatic welcome. His election as President in 1960 was a source of great pride to the Irish People and of some advantage to the Country in its International relations.

When the news broke at home that fateful Friday evening people could hardly believe it. The first reports indicated he had been wounded and that he had been rushed to hospital in Dallas. Then came the terrible confirmation of his death. It was Telefís Éireann broadcaster Charles Mitchel who was given the grim task of breaking the news that Ireland's favourite son was dead. At 7.05pm on November 22, 1963, the nation was stunned into silence when the station broke into a sports programme to report that President Kennedy had been the victim of a shooting.

"We have just heard that an attempt has been made on President Kennedy's life in Dallas, Texas," the veteran newsreader said. "First reports say that he has been badly wounded." Just 20 minutes later a visibly moved Mitchel came back on air to announce: "President Kennedy has been shot dead by an assassin in Dallas, Texas." People simply didn't believe the news, and there were numerous calls to the station seeking confirmation.

http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/how-broadcasters-reported-the-shocking-killing-of-a-president-29758453.html

I can remember this one as a child watching unfold on a black & white TV and the huge level of shock & horror that was felt here at home of the brutal murder of a man that the Irish People saw as one of our own stock.

Monday, 21 November 2022

21 November 1974: The Birmingham Pub Bombings on this day. Two bombs exploded in the British city of Birmingham. The bombs were planted by members of the IRA who gave totally inadequate warnings. Both bombs were planted in pubs in central Birmingham that were about 50 yards apart, the first in the Mulberry Bush at 8.17pm; the second in the Tavern in the Town 10 minutes later. Twenty-one people died, 182 were injured, many horribly so.

Most of the dead and wounded were young people between the ages of 17 and 25, including two brothers: Desmond and Eugene Reilly. One of the victims, 18-year-old Maxine Hambleton, had only gone into the "Tavern in the Town" to hand out tickets to friends for a party. She was killed seconds after entering the pub and had been standing beside the bag containing the bomb when it exploded. Her friend, 17-year-old Jane Davis, was the youngest victim of the bombings. The others who were killed by the bombs were Michael Beasley (30), Lynn Bennett (18), Stanley Bodman (51), James Caddick (40), Thomas Chaytor (28), James Craig (34), Paul Davis (20), Charles Gray (44), Anne Hayes (19), John Jones (51), Neil Marsh (20), Marylin Nash (22), Pamela Palmer (19), Maureen Roberts (20), John Rowland (46), Trevor Thrupp (33), and Stephen Whalley (21)

The was widespread revulsion and outrage at these atrocities, especially in England. This led to a backlash by some people against Irish residents in the UK. In the wake of the bombings a number of people were arrested and charged with organising and planting the devices that exploded.

Six men - ‘The Birmingham Six’ - were convicted of Murder and sentenced to Life Imprisonment. The men - Hugh Callaghan, Patrick Joseph Hill, Gerard Hunter, Richard McIlkenny, William Power and John Walker - were beaten while in police custody and always claimed that they had no part in the bombings and that any confessions were forced from them. Eventually after a long campaign they were declared innocent and freed in 1991. To this date none of the actual perpetrators have ever been convicted.

Tuesday, 15 November 2022

15 November 1985: The Anglo-Irish Agreement was signed by the Irish and British Government at Hillsborough, Co. Down on this day. The Agreement was the most important development in Anglo-Irish relations since the 1920s. Both Governments confirmed that there would be no change in the status of Northern Ireland without the consent of a majority of its citizens. But it also saw recognition by the British that the Irish State had a legitimate interest in the affairs of the North and would be consulted on a regular basis as to what policies would be followed in relation to its governance.

So the Irish Government, through the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Conference and Maryfield Secretariat, was provided with a consultative role in the administration of the Six Counties for the first time. It was this consultative role, accompanied by the continuing conditional nature of the British claim to the North, that caused strong opposition to the Agreement from the unionist population of Ulster. Republicans also opposed the Agreement as falling short of their demands for immediate British withdrawal and a united Ireland.

While the Irish Leader An Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald was chuffed to pull off what in his eyes was a diplomatic coup his co signatory Mrs Thatcher the British Prime Minister was not so sure. She saw the Agreement more as a security issue to get the Irish government to crack down on the IRA rather than as a means towards a full political settlement. She also rightly foresaw that Unionist opposition to the Agreement would be strong and ferocious.

In retrospect the Agreement had mixed success. There was increased co-operation in security issues between the police forces in both jurisdictions and the rise of Sinn Fein was temporarily stalled. But it was to be another 13 long years before the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 laid the foundations for the current political settlement - something that most would consider to be still a ‘work in progress’...

"I had come to the conclusion that I must now give priority to heading off the growth of support for the IRA in Northern Ireland by seeking a new understanding with the British Government, even at the expense of my cherished, but for the time being at least clearly unachievable, objective of seeking a solution through negotiations with the Unionists."

Garret FitzGerald in his autobiography All in a Life (FitzGerald, 1991).

''I started from the need for greater security, which was imperative. If this meant making limited political concession to the South, much as I disliked this kind of bargaining, I had to contemplate it."

Margaret Thatcher in her autobiography The Downing Street Years (Thatcher, 1993).

Monday, 14 November 2022

14 November 1180 AD: The death occurred of St Laurence O’Toole / Lorcan Ua Tuathail at Eu in Normandy on this day. He is the patron Saint of Dublin. He was born in Kildare in about the year 1128 and was educated at the Monastery of Glendalough where he became a prominent member of the religious community there. Being the brother in law of the King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, further enhanced his status.

In 1161 he obtained the key ecclesiastical appointment of Archbishop of Dublin and in the following year was consecrated as such in a great ceremony at Christ Church in the city by Gilla Isu the Primate of Armagh. O’Toole’s elevation was a novelty in that he was the first Gaelic leader of the Church in Dublin and that he owed his position to the See of Armagh and not that of Canterbury in England. The Archbishop was a man of great piety and charity and he founded a number of religious houses including the one of All Hallows where Trinity College now stands. Once a year he retreated to Glendalough where he entered a cave for 40 days to fast and pray.

However when Henry II crossed into Ireland and set up Court in Dublin he was a deft enough operator to ensure that he stayed in the Kings’ good standing. He acted as a go between in the delicate negotiations with Rory O’Connor the King of Ireland and Henry in his role as King of England. Indeed he was one of the signatories of the Treaty of Windsor in 1175 which recognised Henry as ‘Lord of Ireland’ - but not as its King.

In April 1178 he entertained the papal legate, Cardinal Vivian, who presided at the Synod of Dublin. He also attended in Rome the great Third Lateran Council in March 1179. Pope Alexander III had summoned it with the particular object of putting an end to the schism within the Church and the quarrel between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Papacy. About three hundred fathers assembled from the provinces of Europe and some from the Latin east, and a single legate from the Greek church. Laurence O’Toole returned home with the title of Papal Legate, which was a mark of the influence he had gained in Rome.

But his further term in office was to be a short one as in the following year he left Dublin to track down the peripatetic Henry in his wanderings across his patchwork quilt Empire of polities. His mission was to bring urgent matters in Ireland for his consideration. After three weeks of detention at Abingdon Abbey, England he followed Henry II to Normandy. Taken ill at the Augustinian Abbey of Eu, he was tended by Abbot Osbert and the canons of St. Victor in his confinement, and it was there that he breathed his last. His tomb is in the crypt, under the Collegial Church at Eu. Many people still go there to pray. Laurence was canonized in 1225. His remains disappeared during the Revolution but his heart was returned to Ireland where it is in the keeping of Christchurch Cathedral Dublin.

Postscript: 'Lorcán's heart remains in Christ Church Cathedral despite the Irish Reformation, although devotion to saints is more prominent in Roman Catholicism than in the Anglicanism of the Church of Ireland which owns the cathedral. The reliquary was stolen in 2012, with the Dean of Christ Church saying "It has no economic value, but it is a priceless treasure that links our present foundation with its founding father". It was recovered in Phoenix Park in 2018 after a tip-off to the Garda Síochána. Media reported that the unidentified thieves thought it was cursed and caused family members' illnesses'

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorc%C3%A1n_Ua_Tuathail

Sunday, 13 November 2022

Saturday, 12 November 2022

Friday, 11 November 2022

11 November 1918: The Armistice on the Western Front on this day. At precisely 11 O'clock in the morning the First World War came to an end on the Western Front in France and Belgium and the guns fell silent. This was as a result of the activation of the Armistice between Germany and the Allied Powers agreed just days beforehand & only finally signed off at Compiègne in France that very morning.

For Nationalist Ireland the end of the War was greeted with relief rather than jubilation. To many Irish People the War was not their War and even many of those who had joined up had by the time it ended mixed emotions about it all. However it was a different feeling amongst the Unionist population who celebrated with gusto what they viewed as an overwhelming Victory over an Evil Empire.

The Irish Times reported of how Dublin greeted the news:

“The feelings that had been pent up for some years were suddenly let loose and the whole city seemed to go mad with joy,”

It went on to note the profusion of Union Jack flags around the city. By the afternoon, huge crowds had gathered from Sackville Street (O’Connell Street) to St Stephen’s Green. A group of students commandeered a hearse and put an effigy of the Kaiser in the back wrapped in a “Sinn Féin flag”

Irish Times 24 April 2018

In his monthly state of the nation submission to the Dublin Castle authorities, the Inspector General of the Royal Irish Constabulary remarked at the close of November 1918 that news of the armistice had brought ‘a sense of relief to every class of the community but it evokes no universal enthusiasm’.

Capt Noel Drury of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers remembered:

“It’s like when one heard of the death of a friend – a sort of forlorn feeling. I went along and read the order to the men, but they just stared at me and showed no enthusiasm at all. They all had the look of hounds whipped off just as they were about to kill.”

Irish Times 24 April 2018

That morning of the Armistice Eamon De Valera sat in his prison cell in Lincoln Jail England and pondered the significance of the day that was in it. He wrote to his wife Sinéad back in Ireland:

I have just heard the sirens and bells which announce that the armistice with Germany has been signed. It will bring relief to many an anxious heart... The thoughts that occur to me here today would fill volumes—we have leisure for thought calm sober thought—thoughts on the vanities of men and of Empires—vanities which the lessons of this war will not dispel. A hundred years ago ‘twas Napoleon this time ‘twas Germany—whose turn will it be next? …

For the sake of the women of the world at any rate I am glad it is over. They it is who have suffered most. Their imaginings have been far worse than the worst horrors the men have had to endure. Those of the victorious nations will forget for a time their nightmare in the joy of victory but alas for those in the nations that have been vanquished.

http://www.ucd.ie/library/exhibitions/

Many tens of thousands of Irishmen had been killed and wounded in the fighting - perhaps as many as 30,000 dead from this island with many more maimed for life or left psychologically scarred. For those who served in front line units the casualty rate was horrendous, for instance the 2nd Leinsters [a Regular Battalion] lost 88 officers and 1,085 men killed and many times that number wounded in the course of the War.

On the Western Front nearly all those Irishmen who had marched off the War were either dead, wounded, captured or no longer serving in front line units. For instance the 16th ‘Irish’ Division had just one Irish battalion left in its composition. When the end came it was greeted with mute acceptance rather than wild joy.

Of course the War had come to Ireland too in the form of Easter Rising in 1916 and left hundreds dead on the streets of the City and much of the City Centre in ruins. After that any motive that Nationalist Ireland had to support the War was very much diminished. At sea there had been the tremendous loss of life on the Lusitania off Kinsale in 1915 and just weeks before the Wars’ end the Mail Boat Leinster was sunk with heavy loss of life off Kingstown [Dun Laoghaire]. Many smaller boats also met their end plying the Trade routes between Ireland and destinations overseas.

We will never know exactly how many men from Ireland served in the Great War but at a conservative estimate it would be circa 250,000 if numbers who joined the Commonwealth Armies and the US Military are included. Even on the last day of fighting Irishmen serving with the American Expeditionary Force were killed in action. The last man to die that day serving with an Irish Regiment was one George Ellison who died at the town of Mons in Belgium serving with the 5th Royal Irish Lancers - though he was a Yorkshireman! He was also the last British soldier to be killed in action during the First World War. Mons had just fallen to the Canadian Corps and it was there that the British Army had fought its first battle of the war back in 1914.

So as the War ended the Unionists, esp. in the north east of Ireland, had at least good cause for feeling their men's sacrifice had not been in vain. It had been a bloody and costly effort nonetheless. It was clear to everybody that the end of the War meant that new opportunities and new dangers awaited as the troops returned and post war elections beckoned that would prove a watershed in Irish Politics.

But to many of the Nationalists at least their sacrifice was problematical. The set of circumstances that had led John Redmond to advocate Nationalist Ireland’s participation in the War four years beforehand had changed utterly. The men from Nationalist backgrounds who had been publicly cheered to the Fronts in 1914 and 1915 could expect only a muted response when they now came home.

There could be no doubt that Ireland on 11 November 1918 was a politically very different place than just over four years earlier on 4 August 1914 when War was declared on Germany. To this day the Great War resonates through European & Irish History as the catalyst for so much that followed from its terrible and costly path...

Thursday, 10 November 2022

Tuesday, 8 November 2022

8 November 1960: The Niemba Ambush in the Congo on this day. An eleven-man Irish patrol under Lt Kevin Gleeson was ambushed by Baluba tribesmen at a river crossing near the village of Niemba, in the Congo. The patrol was surrounded by up to 100 African warriors who attacked them with primitive weapons and killed all but two of their number. Though well armed with 2 Bren guns, 4 Gustaf sub-machine guns and 4 rifles it seems the men were taken unawares and unable to organise any effective resistance before been overcome. One of the party, the Medical Officer, carried no weapon at all. Nor did they have any wireless equipment to which to signal their plight. Their opponents carried bows and arrows, spears, panga knives and clubs. The action had commenced at approximately 3 p.m. local time. The first search party left Albertville at 10.30 p.m., arrived at Niemba at 3.45 a.m. and was on the scene of the ambush about first light on 9 November.

The remains of eight of the victims were found almost immediately but those of Trooper Anthony Browne could not be located. An intensive search for him proved fruitless and he was officially posted "missing - presumed dead". It was not until a year later almost to the date that Trooper Brown's body was found. Trooper Brown had survived the ambush and wandered in the jungle until he came upon some Baluba women who gave him up to a party of Baluba men, who murdered him.

Two of the Platoon survived to tell the story of the ambush. They were Troopers Thomas Kenny and Private Joe Fitzpatrick.

Fitzpatrick recalled that:

The air was suddenly black with a shower of arrows, and the Buluba let out blood-curdling yells that sounded like a war cry and rushed down the road like madmen, jumping in the air and waving their weapons.

The names of the men who were killed in the ambush were:

Lt Kevin Gleeson (Co)

Sgt Hugh Gaynor

Cpl. Liam Duggan

Pte.Matthew Farrell (Unarmed Medic)

Pte Gerard Kileen

Cpl. Peter Kelly, Driver

Tpr Thomas Fellell

Pte. Michael McGuinn

Murdered on Capture:

Tpr Anthony Browne

Survived:

Pte Joseph Fitzpatrick

Pte Thomas Kenny

The death of nine Irish soldiers on the Irish Army’s first large scale overseas mission shocked the Nation when word of this terrible massacre reached home. Many recalled the hope and pride that had been felt by the Irish People when the soldiers had departed from Ireland just a few short months beforehand.

The Memorial Cross (above) was erected by their comrades at the place of the ambush to commemorate their sacrifice in the service of the United Nations.

Monday, 7 November 2022

7 November 1980: The death on this day of Frank Duff, Founder of the Legion of Mary. Frank Duff was born in Dublin, Ireland, on June 7, 1889. 1917 Frank Duff came to know the Treatise of St. Louis Marie de Montfort on the True Devotion to Mary, a work which changed his life completely.

He entered the Civil Service at the age of 18. At 24 he joined the Society of St. Vincent de Paul where he was led to a deeper commitment to his Catholic faith and at the same time he acquired a great sensitivity to the needs of the poor and underprivileged. Along with a group of Catholic women and Fr. Michael Toher, a priest of the Dublin Archdiocese, he formed the first branch of what was to become the first praesidium of the Legion of Mary on September 7, 1921. The first meeting was attended by 13 women and 2 men. The Legion of Mary is a lay catholic organisation whose members are giving service to the Church on a voluntary basis in almost every country.

Its twofold purpose is the spiritual development of its members and advancing the reign of Christ through Mary. The first legionaries were women. Using his skills as a draftsman picked up from his days in the Civil Service, Duff compiled a handbook that defined the legion as a voluntary body "at the disposal of the bishop of the diocese and the parish priest for any and every form of social service and Catholic Action which these authorities may deem suitable to legionaries and useful to the welfare of the church". But Duff was a man with a mind of his own. He kept his distance but knew where the lines were - anyway his quite diplomacy worked and the Legion went from strength to strength.

In 1925 he was instrumental in getting the notorious Red Light district of ‘The Monto’ in Dublin closed down and in helping many of the girls who worked as prostitutes there to start a new life. He spent a lifetime in devotion to Mary the Mother of Christ and through that inspiration in helping others less fortunate than himself. He and his dedicated helpers built up a huge Catholic organisation that was not controlled by the Hierarchy but worked with it to spread the Word.

In 1965 Pope Paul VI invited Frank Duff to attend the Second Vatican Council as a Lay Observer, an honour by which the Pope recognized and affirmed his enormous work for the lay apostolate. By the time of his death Duff, a life-long bachelor committed to celibacy, presided over a worldwide spiritual empire. He died at his home in Brunswick St Dublin and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Today, the Legion of Mary has an estimated four million active members -- and 10 million auxiliary members -- in close to 200 countries in almost every diocese in the Catholic Church Worldwide.

Sunday, 6 November 2022

6 November 1649: General Owen Roe O’Neill/Eoghan Rua Ó Néill died at Cloughoughter/ Cloch Uachtar Castle in County Cavan on this day. He was the leader of the last Gaelic Army of the North and one of Ireland’s greatest Generals. He was born circa 1585/90 and was the son of Art Mac Baron O'Neill and the nephew of the Great Aodh O'Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, who led the Catholics during the Nine Years War (1594-1603).

He was sent to Spain at an early age and joined the Irish Brigade of the Spanish Army. He was an able and talented soldier and destined to command at a high level. He never forgot his Homeland though and kept in contact with those in Ireland who wished to overthrow the religious and civil persecutions that the Irish Catholic People suffered under. His greatest test came in 1640 when he was in command of the City of Arras (then part of the Spanish Netherlands) that was besieged by an overwhelming French Army. With just 1,500 men he held out against the odds for eight long weeks despite many assaults on the Citadel. Forced eventually to ask for terms he was allowed to march out with the Honours of War.

But the following year the Rising of 1641 erupted and he decided that his place was back in Ireland and the head of Irish soldiers. Accompanied by a cluster of trusted officers he sailed in a tiny fleet to make it back here in July 1642. Shocked by the mayhem and indiscipline he encountered he quickly reformed the men placed under his care into a cohesive and efficient armed force. Despite this he was defeated at the Battle of Clones in 1643 but he learnt his lesson of never again meeting the enemy on anything less than favourable terms. In 1645 the Papal Nuncio, Archbishop Rinuccini, arrived with Arms & specie to breathe life into the Confederate Armies, of which O’Neill’s force constituted a semi-autonomous component. This was to be a turning point in the struggle to gain mastery over the North.

In the early summer of 1646 he achieved his greatest Victory when he took the field against the Anglo-Scots of Ulster under the command of Sir Robert Monro. At the Battle of Benburb on 5 June of that year he defeated and overwhelmed a British Army led by Monro. It was the biggest set-piece battle of the Confederate War and a major setback for the British in Ulster, but, split by internal divisions and engaged in futile negotiations with the Duke of Ormond, the Confederates failed to follow up the military advantage of O'Neill's victory. The Catholics were hopelessly divided between those who wished to reach an agreement with King Charles I to allow for a level of toleration for the Catholic religion and those who would settle for nothing less than the removal of all impediments to the open practise of Catholicism.

Such internal pressures eventually led to what was in effect an internal Civil War in which Owen Roe O’Neill was called upon to move south to back the Papal Nuncio in his implacable opposition to the Peace Treaty with the Protestant Viceroy Ormond. In September 1646, O'Neill marched to Kilkenny to support Rinuccini, who then forced the Supreme Council to agree to a Confederate attack on Dublin with the Ulster and Leinster armies. Owen Roe O’Neill’s Ulster Army swept down upon the plains of Meath, burning homesteads and destroying the crops in an effort to hamper the Royalist War effort. But the two pronged assault on Dublin fizzled out as the City was well protected by strong walls and a determined garrison. The onset of Winter then put a stop to any chance of a prolonged Siege.

During 1647, moderate members of the Supreme Council succeeded in relegating O'Neill to service in Connacht and relied upon Preston to protect Kilkenny with the Leinster army. In 1648 the Confederates again fell out amongst themselves. O'Neill remained loyal to Rinuccini. In June 1648, he declared war on the Supreme Council and marched against Kilkenny. Although he failed to capture the Confederate capital, he spent most of the summer pillaging the surrounding country and manoeuvring against Inchiquin and Confederate forces in Leinster. In January 1649 Archbishop Rinuccini departed from Ireland in despair. O'Neill refused all approaches to join the Royalist-Confederate coalition because Ormond would not commit himself to promising the restoration of Irish lands in Ulster as O'Neill demanded.

By then King Charles I had been executed and Oliver Cromwell was ready to lead a well equipped army to Ireland to attempt a Re Conquest. Despite negotiations O’Neill was wary of the shaky coalition of Catholic Confederates and Protestant Royalists led nominally by the Duke of Ormond - a rather shady character. Neither side trusted the other and O’Neill was effectively isolated from events in the rest of the Country. Indeed so weak had become O’Neills position and so starved was he of supplies that he made an arrangement with the Parliamentarians Colonel Monck and later with Sir Charles Coote in order to stop the lands he held been overrun by the Ulster Scots, who now fought under the King’s Charles II banner.

General O’Neill, perhaps unwisely, took up an invitation to dine in Derry with Sir Charles Coote, the Governor of the City. Soon afterwards he became ill, took a fever and died. His followers quickly suspected treachery and perhaps they were right. If so it was a devious but effective way of the English Parliament to rid itself of one of the most able soldiers this Country has ever produced. He is buried in an island in Lough Oughter in Cavan.

Saturday, 5 November 2022

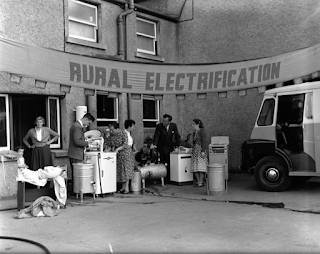

5 November 1946: The start of the Rural Electrification Scheme in the Irish Free State on this day. This major project began in a field at Kilsallaghan in north county Dublin[above]. Kilsallaghan was the 1st rural area in Ireland out of 792 so designated to receive electricity under the scheme. The Rural Electrification Scheme employed up to 40 separate units of 50-100 workers, spread across 26,000 square miles. By November 1961 280,000 rural premises were connected, at a cost of over £30,000,000. The purpose was to roll out the benefits of electricity to every household and farm in the State. The task was entrusted to the Electricity Supply Board (established 1927) and the mammoth task entailed the purchase over one million wooden poles from Finland. Over 75,000 miles of wire were also needed.

‘The electrification of rural Ireland had been envisaged since work first began on the Shannon Scheme in 1925. Dr Thomas McLaughlin, the founding father of ESB, believed that rural electrification represented ‘the application of modern science and engineering to raise the standard of rural living and to get to the root of the social evil of the “flight from the land”.

‘However, the financial resources were not available to extend electricity to rural Ireland in the first days of the newly formed Irish free state and in the 1920s and 1930s. Electricity from the Shannon Scheme was supplied to roughly 240,000 premises in towns and cities only, leaving over 400,000 rural dwellings without power. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, ESB and the government began working on broad plans for rural electrification, and the state agreed to subsidise its roll out. However, the outbreak of World War II in 1939 delayed the process, and work could not start on the scheme until after its end in 1945.’...The last area to receive electricity was the remote area of Blackvalley, Co. Kerry, in 1978.

https://esbarchives.ie/2016/03/23/life-before-and-after-rural-electrification/

The benefits of electricity was of course huge. It was something that just about every home and farmstead in the State wanted with only the very odd one refusing to be connected. Up until then the managing of a household or farm had been a hugely labour intensive operation for both men and women. Everything from cooking to washing to heating was pure manual work.

‘Activity on the farm and in rural households was dictated by the availability of daylight. After dark, limited lighting was provided by oil lamps or candles. Water had to be drawn from a well, and carried home by foot or by cart. Clothes had to be washed by hand, or with a hand-powered ‘wringer washer’. Heating and cooking depended on solid fuel, such as timber and turf, often cut and harvested by the family. Cooking was confined to an open hearth or range. Food safety was difficult to ensure without any form of refrigeration, a particular difficulty on the farm and in the dairy. Industrial development was not feasible without a supply of electricity.’

https://esbarchives.ie/2016/03/23/life-before-and-after-rural-electrification/

Today we live in a world where the lack of electricity in our daily lives is unthinkable. But there are still Irish households today where the oil lamp is not a source of curiosity but a memento of a time when they could not make their way about their house after dark without one.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.tif.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)