11 November 1918: The Armistice on the Western Front on this day. At precisely 11 O'clock in the morning the First World War came to an end on the Western Front in France and Belgium and the guns fell silent. This was as a result of the activation of the Armistice between Germany and the Allied Powers agreed just days beforehand & only finally signed off at Compiègne in France that very morning.

For Nationalist Ireland the end of the War was greeted with relief rather than jubilation. To many Irish People the War was not their War and even many of those who had joined up had by the time it ended mixed emotions about it all. However it was a different feeling amongst the Unionist population who celebrated with gusto what they viewed as an overwhelming Victory over an Evil Empire.

“The feelings that had been pent up for some years were suddenly let loose and the whole city seemed to go mad with joy,” The Irish Times reported of how Dublin greeted the news.

It went on to note the profusion of Union Jack flags around the city. By the afternoon, huge crowds had gathered from Sackville Street (O’Connell Street) to St Stephen’s Green. A group of students commandeered a hearse and put an effigy of the kaiser in the back wrapped in a “Sinn Féin flag”

Irish Times 24 April 2018

In his monthly state of the nation submission to the Dublin Castle authorities, the Inspector General of the Royal Irish Constabulary remarked at the close of November 1918 that ‘news of the armistice’ had brought ‘a sense of relief to every class of the community but it evokes no universal enthusiasm’.

Capt Noel Drury of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers remembered:

“It’s like when one heard of the death of a friend – a sort of forlorn feeling. I went along and read the order to the men, but they just stared at me and showed no enthusiasm at all. They all had the look of hounds whipped off just as they were about to kill.”

Irish Times 24 April 2018

That morning of the Armistice Eamon De Valera sat in his prison cell in Lincoln Jail England and pondered the significance of the day that was in it. He wrote to his wife Sinéad back in Ireland:

I have just heard the sirens and bells which announce that the armistice with Germany has been signed. It will bring relief to many an anxious heart... The thoughts that occur to me here today would fill volumes—we have leisure for thought calm sober thought—thoughts on the vanities of men and of Empires—vanities which the lessons of this war will not dispel. A hundred years ago ‘twas Napoleon this time ‘twas Germany—whose turn will it be next? …

For the sake of the women of the world at any rate I am glad it is over. They it is who have suffered most. Their imaginings have been far worse than the worst horrors the men have had to endure. Those of the victorious nations will forget for a time their nightmare in the joy of victory but alas for those in the nations that have been vanquished.

http://www.ucd.ie/library/exhibitions/

Many tens of thousands of Irishmen had been killed and wounded in the fighting - perhaps as many as 30,000 dead from this island with many more maimed for life or left psychologically scarred. For those who served in front line units the casualty rate was horrendous, for instance the 2nd Leinsters [a Regular Battalion] lost 88 officers and 1,085 men killed and many times that number wounded in the course of the War.

On the Western Front nearly all those Irishmen who had marched off the War were either dead, wounded, captured or no longer serving in front line units. For instance the 16th ‘Irish’ Division had just one Irish battalion left in its composition. When the end came it was greeted with mute acceptance rather than wild joy.

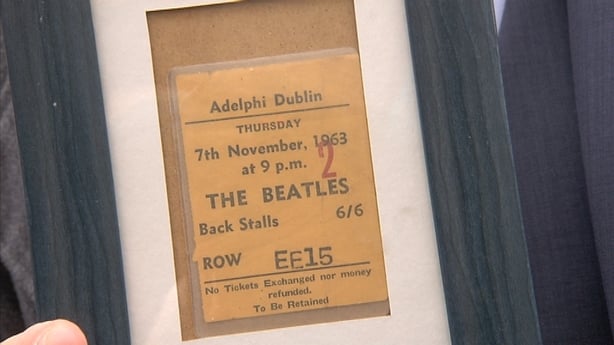

Of course the War had come to Ireland too in the form of Easter Rising in 1916 and left hundreds dead on the streets of the City and much of the City Centre in ruins. After that any motive that Nationalist Ireland had to support the War was very much diminished. At sea there had been the tremendous loss of life on the Lusitania off Kinsale in 1915 and just weeks before the Wars’ end the Mail Boat Leinster was sunk with heavy loss of life off Kingstown [Dun Laoghaire]. Many smaller boats also met their end plying the Trade routes between Ireland and destinations overseas.

We will never know exactly how many men from Ireland served in the Great War but at a conservative estimate it would be circa 250,000 if numbers who joined the Commonwealth Armies and the US Military are included. Even on the last day of fighting Irishmen serving with the American Expeditionary Force were killed in action. The last man to die that day serving with an Irish Regiment was one George Ellison who died at the town of Mons in Belgium serving with the 5th Royal Irish Lancers - though he was a Yorkshireman! He was also the last British soldier to be killed in action during the First World War. Mons had just fallen to the Canadian Corps and it was there that the British Army had fought its first battle of the war back in 1914.

So as the War ended the Unionists, esp. in the north east of Ireland, had at least good cause for feeling their men's sacrifice had not been in vain. It had been a bloody and costly effort nonetheless. It was clear to everybody that the end of the War meant that new opportunities and new dangers awaited as the troops returned and post war elections beckoned that would prove a watershed in Irish Politics.

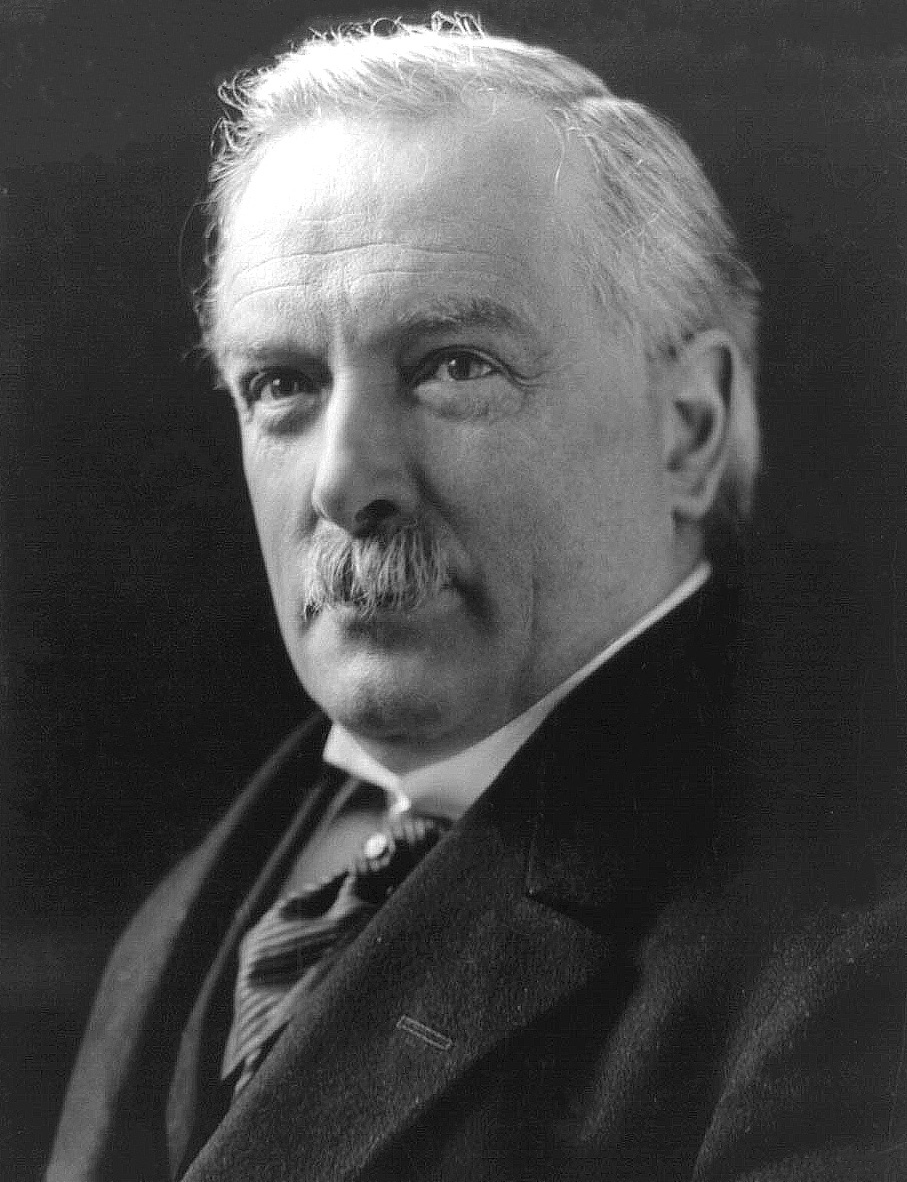

But to many of the Nationalists at least their sacrifice was problematical. The set of circumstances that had led John Redmond to advocate Nationalist Ireland’s participation in the War four years beforehand had changed utterly. The men from Nationalist backgrounds who had been publicly cheered to the Fronts in 1914 and 1915 could expect only a muted response when they now came home.

There could be no doubt that Ireland on 11 November 1918 was a politically very different place than just over four years earlier on 4 August 1914 when War was declared on Germany. To this day the Great War resonates through European & Irish History as the catalyst for so much that followed from its terrible and costly path...