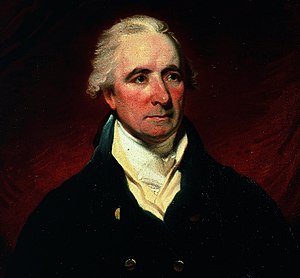

7 July 1816: The great Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan died on this day. He died in the City of London in impoverished circumstances.

Sent to be educated at Harrow by his father he completed his education before he eloped and married Elizabeth Linley and with her modest fortune behind him he established himself in London and began his career as a playwright. In the same year, 1772, Richard Sheridan, at the age of 21, eloped with and subsequently married Elizabeth Ann Linley and set up house in London on a lavish scale with little money and no immediate prospects of any—other than his wife's dowry. The young couple entered the fashionable world and apparently held up their end in entertaining.

He enjoyed some success with his first major play The Rivals that was performed at Covent Garden in 1775. However his most famous play is The School for Scandal which was first performed at Drury Lane in May 1777. It still ranks as one of the greatest comedies of manners of the English stage. Having quickly made his name and fortune, in 1776 Sheridan bought David Garrick's share in the Drury Lane patent, and in 1778 the remaining share. His later plays were all produced there.

However his later literary career was more of a business venture rather than as an original playwright and Sheridan switched a lot of his attention to English Parliamentary politics where he supported the Whigs. He entered parliament for Stafford in 1780, as the friend and ally of Charles James Fox. He opposed the American War and was instrumental in the impeachment of Warren Hastings. An excellent public speaker his voice and eloquence commanded attention whenever he rose in the House. Initially a supporter of non intervention against France as the Revolution took hold he was more sanguinary in approach as Napoleon rose to dominance.

He was as it happens one of the few MPs at Westminster to oppose the Act of Union. When the Whigs came into power in 1806 Sheridan was appointed treasurer of the Royal Navy, and became a member of the Privy Council. Throughout his parliamentary career Sheridan was one of the close companions of the Prince of Wales (the later King George IV). He tried though to distance himself from the suggestion that he was the Prince’s advisor or even a mouthpiece for him. He did however defend the controversial Royal member in parliament in some dubious matters of payment of debts.

In 1809 his beloved Drury Lane Theatre burned down. Legend has it that on being encountered drinking a glass of wine in the street while watching the fire, Sheridan was famously reported to have said:

A man may surely be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside.

His last years were marred by personal and financial troubles as he lost his parliamentary seat, fell out with the Prince and was pursued by numerous debtors. In December 1815 he became ill, and was largely confined to bed. His last few weeks were spent in almost total destitution as his funds ran out. He died on the 7th of July 1816, and was buried with great pomp in Westminster Abbey. His funeral was attended by dukes, earls, lords, viscounts, the Lord Mayor of London, and other notables.

ADD

Overview

Mary Swanzy (1882-1978) is a unique Irish artist. Her level of achievement, world travel and original thinking is unmatched in Irish art, yet this is the first retrospective of her work in 50 years. Born in the late Victorian era, by her early twenties Swanzy had mastered the academic style of painting. She witnessed the birth of Modern art in Paris before the First World War and her work rapidly evolved through the different styles of the day, each of them interpreted and transformed by her in a highly personal way.